Artificial Stupidity: One Prompt at a Time

"Frictionless AI" isn’t making you smart. It is consistently eroding your cognitive ability, creative integrity, and ethical awareness

Prompting, especially in the recent past, has become “code” for interacting with generative artificial intelligence in just about any shape and form. Prompting consists of reasonably low-effort concise (or not) linguistic cues that elicit fluent, contextually rich responses from generative models.

The increasingly addictive ease of this interaction can probably be best described as “seductive”. With a few cave-man grunts, one can produce essays, poems, lesson plans, software, websites, applications or strategic documents.

And don’t get me wrong, I am the biggest advocate of AI-enabled greatness and technology for a better life. That said, intelligence now feels on-demand, commoditized and accessible to all; ambient noise if you will.

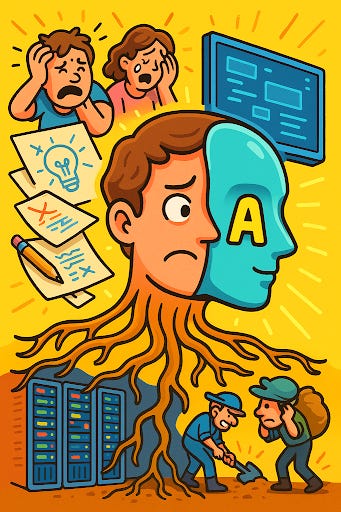

But prompting certainly doesn’t come without a cost. Recent research from cognitive science, AI ethics, and sociotechnical systems reveals the tax we pay when we allow prompting to take over various functional aspects of our lives: decline in cognitive engagement, creative agency, and ethical attentiveness.

The illusion of intelligence offered by generative AI systems risks attenuating our own intelligence.

What is infinitely worse than thinking less, however, is to value and glamourize thinking less.

The ubiquitous use of generative AI subtly displaces the value we collectively assign to thinking by normalizing (nearly) instant outputs. It makes reflection an act of inefficiency and curiosity optional or redundant. Leaving us to meet in the brain rot of synthetic sameness.

How did we prompt ourselves into declining cognitive ability?

Research in cognitive psychology and neuroscience consistently shows that effortful processing, actively engaging with complex, ambiguous problems, is critical for long-term learning, conceptual insight, and memory formation. Generative AI interfaces, by contrast, offer users fluent responses with minimal (read no) cognitive investment.

This shift is significant.

When users rely on AI to summarize arguments, generate hypotheses, or complete creative work, they may experience what researchers call “cognitive offloading”; the outsourcing of memory and problem-solving to external systems. While offloading is often beneficial, excessive reliance can impair metacognition. Often considered intrinsic to being “human” is our ability to monitor and evaluate our own thinking.

Dellermann et al. found that users collaborating with generative AI in problem-solving tasks were more likely to accept inaccurate or biased information without scrutiny, displaying what the authors term “automation-induced cognitive inertia”.

Cognition, although perhaps the most visibly affected, is unfortunately not the only human faculty under pressure. The creative process, too, is being tuned in unsettling ways (and not for the better).

Co-Creation Replaced by Creative Substitution?

In education, design, and creative industries, prompting was and still is considered a possible mode of co-creation. But there is a critical distinction between amplifying human creativity and replacing it. Generative AI systems appear an extremely convenient method of jumping the gun and removing the “unproductive” aspects of the creative process: uncertainty, frustration, and iterative failure.

Yet those very aspects are essential, rudimentary and pedagogical. Creativity research emphasizes the role of productive struggle, incubation, and failure tolerance as core drivers of original work.

Prompting, while fast and fluent, may short-circuit this crucial developmental arc.

Moreover, the outputs of large-scale language models are inherently statistical; they are optimized for coherence and likelihood, not originality. This sameness emerges not from the lack of fluency, but from an overabundance of it. It feels much like polished predictability that rewards the familiar and sidelines the experimental. When creativity becomes a matter of selecting from high-probability outputs, the risky, radical, or unresolved ideas that fuel genuine innovation are often left behind.

In this sense, prompting doesn’t just influence what we create, but how we think about creativity itself; as something frictionless, fast, and easily rendered, rather than exploratory, uncertain, and deeply human. As we begin to depend on AI for brainstorming, ideation, and revision, we risk narrowing creative possibilities to what the model already knows, thus reinforcing “synthetic sameness”.

The Illusion of Intelligence: Fluency, Bias, and Disengagement

What can be worse than cognitive decline and discarded creativity?

Perhaps the most dangerous illusion of prompting is epistemic: the belief that the AI’s fluent output reflects understanding, accuracy, or insight. The knowledge illusion and the argument for thinking for ourselves (once in a while, at least) is very well explored here.

Cognitive science warns against the fluency effect, our tendency to judge ideas as more truthful or valuable if they are processed more easily. Generative AI’s surface polish enhances this bias, making it harder for users to question or investigate its content. This is especially true when models offer confident, articulate responses even when the underlying information is demonstrably false or misapplied.

Ethically, prompting also encourages a passive posture. When machines provide the framing, content, and language for a given task, human users may feel less responsible for the implications. This is a problem of moral distancing, an ethical diffusion that grows when tools obscure the sources, biases, or stakes of their outputs.

The frictionless interface further conveniently hides exploitative systems; labor, environment, and power.

Invisible Infrastructures, Extractive Logics

Behind each AI-generated response lies an entire sociotechnical ecosystem marked by labor, inequality, and material cost. The myth that AI is “immaterial” belies the fact that these tools depend on vast amounts of training data, data-center energy, water for cooling, and crucially, human labor.

A 2023 investigation by Time revealed that OpenAI contracted workers in Kenya for less than $2/hour to label and filter harmful content, often under traumatic psychological conditions. Their work is essential to the safety of systems like ChatGPT, but remains conveniently invisible to most users.

Similarly, AI training and inference consumes enormous amounts of electricity and water. In some U.S. regions, data centers now represent a major stressor on local energy and aquifer systems. Each prompt, while cognitively light, may carry a heavy ecological footprint.

Kate Crawford, in her book Atlas of AI, describes this system as fundamentally extractive; pulling value from human labor, cultural artifacts, and natural resources, while presenting a seamless user experience that hides these costs. This is why reclaiming our understanding of intelligence is more than a technical concern, it’s also a moral, political and intellectual one.

Rethinking Intelligence, Reclaiming Agency

The rise of generative AI invites us to reconsider what we mean by “intelligence.” The danger is not just that prompting makes us think less. It encourages us to value thinking less, and to replace the entirety of human intelligence with efficient simulation.

If intelligence becomes synonymous with fluency, speed, and convenience, we risk marginalizing the more fragile, time-bound, and reflective aspects of thought. Human intelligence thrives in messiness; in uncertainty, contradiction, and emotion.

These are unfortunately not qualities generative AI is designed to reproduce. Rather than abandoning these tools, we need to reframe how we use them. Prompting should be a site of co-reflection, not passive consumption. It should support, and not substitute, intellectual effort. To do that, we must remain aware of the scaffolding behind the system: the human labor, the training data, the power structures, and the limitations of the model.

Intelligence Beyond Simulation

We are not becoming stupid necessarily by using AI but more because we are thinking less of thinking. We are unfortunately also becoming more vulnerable to thinking shallowly, creating predictably, and acting without context, if we allow machines to define what intelligence looks like.

Prompting feels like progress because it’s easy. But real thinking is rarely easy. It is effortful, uncertain, sometimes agonizing.

If we want to remain intellectually and ethically alive in an age of fluent machines, we must prompt not only the system but ourselves.

Not for better outputs, but for better questions.

Thank you, Promit, for this wonderful piece of pure and clear human intelligence and cognitive effort. I completely agree that using machines to replace or simulate our intelligence is sadly heading in the wrong direction, especially when the true intention behind technological advancement should be to empower humanity, not replace its deep power of reflection. AI is a powerful tool when used to solve problems that truly matter. As you say, our ability to respond creatively, ethically, and intuitively is something machines have not, and may never achieve.

I fear that if we, as you suggest, don’t prompt ourselves to ask better questions and instead rely solely on AI for all the answers, the future will become very plain and sad: a place where everyone speaks, acts, and expects the same things and the same answers, because we’ve been trained by the very algorithmic models we were originally trying to train. A future shaped by algorithmic sameness is one where diversity of thought and creativity could be lost forever.

We also need to speak more loudly about the ethical implications and hidden costs of building these technologies, thank you for bringing this up. This conversation is not just timely; it’s essential for the future of humanity.

Could not agree more with this. Thanks to Phi/AI for putting some real perspective on the tendency of creative people to 1) use new software built on AI that “does the work” for them and 2) fear that they will be replaced by AI (for the same reasons they begin using the software). There’s no replacement for carrying the “cognitive burden.” It’s what makes our work better (and maybe great). As creative people, we need to figure out how much of it we have to carry and how much we can offload.