The Thinking Person's Guide to Not Getting Dumber with AI

“If the little grey cells are not exercised, they grow the rust.”

- Hercule Poirot, ABC Murders

At this point, we’ve all heard about the MIT viral study - that ChatGPT is making us dumber. Using these systems is not free - while it may save time in the short term, the long term cognitive cost of outsourcing thinking to these LLMs is a cost I’m not willing to pay.

As I wrote in my last piece, there’s an illusive pull to use these tools. Their ostensibly endless capacity for new ideas which appear fully developed and far better than the ramshackle, loose ideas that spool in one’s own head. Yet, the danger lies in allowing these tools to make conclusions and decisions for you.

Two recent interviews with arguably some of the most influential people in this AI space should provide us lay people with the direction to use these tools. Both Deep Mind’s CEO Demis Hassabis and NP26’s CPO Mayur Kamat shared on podcasts that they are not using AI for critical thinking, with Kamat offering a more hard-lined take - saying he had not found “good use cases for his job” yet. AI still cannot do true out of the box thinking - it can solve conjectures, not conjure them up. Kamat said it well - “What remains the domain of humans is decision making and taking the brunt of the impact of the decisions you make”.

Co-creating with Technology - A Brief History

This said, refraining from using these tools is not the answer, as humans and technology have worked together to co-create for hundreds of years. Interestingly, we can look to the Luddites for inspiration on how to act. Yes, that group of people who destroyed textile machinery in 19th century Britain. Popular culture has cast them as backward-looking technophobes who simply opposed progress, but this couldn't be farther from the truth.

The Luddites were not fighting against the technology itself - they were fighting against how it was being deployed and what human capacities it's displacing. These skilled weavers, spinners, and knitters had used similar technology before - they were revolting against factory owners using new machinery specifically to replace them, produce inferior products, and concentrate wealth among a few factory owners.

Sound familiar? Today's AI deployment patterns echo these same concerns. The World Economic Forum's 2025 Future of Jobs Report found that 40% of employers expect to reduce their workforce where AI can automate tasks, particularly targeting entry-level and white-collar roles - not because the technology can't augment human work, but because it's cheaper to replace workers entirely.

Yet refraining from these tools isn't the answer. Instead, we can learn from how humans and technology have successfully collaborated for centuries.

I came across a collection of essays while researching this piece called Thinking with AI. It’s written by thinkers across the newly minted Critical AI studies field and opens with a powerful quote:

The foremost of human faculties is the power of thinking. The power of thinking can be assisted either by bodily aids or by mental aids.

—Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, On the Organon or Great Art of Thinking, 1679

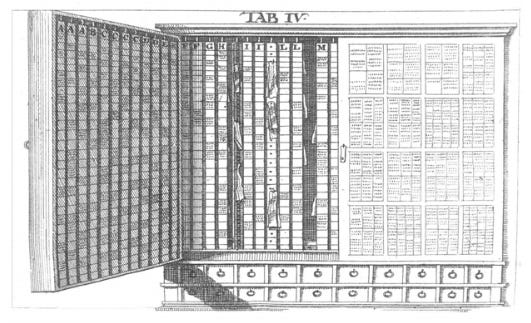

In Markus Krajewski's essay "Intellectual Furniture: Elements of a Deep History of Artificial Intelligence”, he highlights two famous ‘assisted thinking’ note-taking examples: Leibniz’s Scrinium Litteratum and Niklas Luhmann's Zettelkasten. Both are technologies that use physical storage with indexing systems to make ideas retrievable and cross-referencable. What made them ingenious was that the indexing function enabled the user to discover and explore unexpected connections between ideas.

The indexing systems worked differently. Leibniz could file a single idea under multiple headings, creating and revealing natural intersection points. Luhman used an alphanumeric system (1, 1a, 1b, 1b1) that let him insert new ideas anywhere in his existing structure, even years later.

Bringing the Zettlekasten and Scrinium Litteratum into the digital age, we see their offspring through the personal knowledge management systems like Obsidian and Notion that have exploded in popularity. The emphasis on backlinking to create visual graphs of connected ideas clearly shows their lineage to these historical precedents.

All these assisted thinking tools are designed to externalize one’s inner thoughts, see them in the light of day, and expose them to interrogation.

Yet, here’s the crucial difference: the human is still front and center, driving the thinking. These systems provide the serendipity to pull together seemingly unconnected ideas, but they always required active input from the thinker - Leibniz’s scraps of paper, Luhmann’s handwritten cards, Obsidian markdown files. Most importantly, these connections had to be articulated by the thinker. They didn’t emerge fully formed in cogent sentences that seemed good enough to copy/paste. This friction, this pause, is what LLMs are taking away from us.

Like the line from Samuel Taylor Coleridge's poem The Rime of the Ancient Mariner “Water, water everywhere, nor any drop to drink", we might update it today to, “data, data everywhere, but not a thought to think.”

The question is: when to use AI, and how to prevent “the little grey cells go to rust?”

Thinking with AI: Keeping Your Brain in the Loop

The MIT study revealed something telling that got less attention - that users felt no ownership of their AI-generated work and couldn’t quote from it later. I referred to this icky feeling in my last piece about how I feel like I’m cheating when I’m using AI. It feels like, and arguably is, plagiarism if I wholesale copy text that AI has generated and pass off as my own.

The salve for this icky feeling is making deliberate decisions about when to use AI and to what end. Think strategically how to use AI to speed up, and when to pump the brakes and slow down to absorb and grapple with what I’ve found.

Warning signs that you’re outsourcing too much thinking: you can’t explain the concept in your own words, you can’t recall what you just pasted wrote, you can’t remember how you arrived at a conclusion, and lastly - you just feel like you’re cheating (and we all know how that feels).

Here’s the thing: AI makes the learning feel easy, and when something is easy, we assume we already know it. We need to insert deliberate friction into our learning process to avoid the illusion of competency trap.

This is where self-regulated learning comes in, paying attention and regulating how you think and learn. John Flavell introduced this concept of metacognition in the 1970s which is “thinking about thinking”. It entails monitoring, regulating, and evaluating one’s thinking at each phase of the learning process: Planning, Performance, and Reflection.

You’ve likely done this while reading this article. Had to re-read Scrinium Litteratum several times to pronounce it correctly? Did you google Luddites to check if I was wrong about the actual definition? That’s self-regulated learning in action.

Self-regulated learning with AI

What does this look like in practice? Here’s how I’m currently using AI across the three phases of learning.

Planning: Getting to the starting line

Need: Getting clear on what I want to accomplish.

Action: 5 minutes of brain dump talking into a voice note app about what I’m trying to learn, do, or figure out. This isn’t polished; it’s just getting the messy thoughts out of my head. Then, I dump the AI transcription into Claude.

Benefit: Claude helps me pull out the key points and map my route. It’s like having a thinking partner who can take my scattered ideas and help me see the structure underneath. Once I have that skeleton, AI becomes my research accelerator - quickly finding examples, definitions, opposing arguments, or helping me understand concepts I don’t know. This exploration phase is where AI’s speed really shines, letting me gather information faster so I can spend more time on the deeper work.

Performance: The tricky middle ground

I’ll be honest - this is where I struggle most with using AI without feeling icky about it. The performance phase is output and action, which makes it feel most like “cheating” if I’m not careful.

Need: Understanding concepts in my own words and stress testing opinions, arguments, and conclusions

Action: Practicing “elaborative interrogation” using Claude, a well-studied technique which pushes you to make connections across ideas you are trying to learn by asking you to explain how these ideas work individually, how they connect together, how they work (or don’t) together.

Benefit: Claude validates my responses, and helps me build on them and explore from different angles. When I think I understand something, I ask it to push me with “again” - to explain it differently, give me another example, make me work through it one more time. This keeps me from getting too comfortable with my first take on something. It’s like having a patient conversation partner who won’t get tired of me working through ideas out loud.

Reflection: Copy editor and what’s next

Need: Editing and refining my work and providing instruction on how to improve

Action: Use Claude as my personal copy editor focused on my specific weaknesses.I’ll ask it to tighten my writing without changing my voice, or to reorganize sections that feel jumbled. This is feedback I’d typically ask a human editor for, but AI can provide it instantly.

Benefit: This lets me lean into my strengths while getting targeted help with my weak spots. Instead of generic editing advice, I get feedback tailored to my specific blind spots, all while maintaining ownership of my voice. I need to choose to accept edits, turns of phrase, etc. I ask myself, does this reflect what I am trying to say?

Thinking about thinking, while thinking with AI

“Poirot," I said. "I have been thinking."

"An admirable exercise my friend. Continue it.”

Using external tools to think is not novel as explained earlier. It's been a critical driver of human capacity for centuries. AI has just made it easier, while gaining the insidious power to actually stop us from thinking.

We need to resist the urge of ease, which turns over our thinking autonomy to an external tool which is still a black box for how it works. Resisting ease is not something humans do well - look at how quickly pastries get eaten up at any office.

The key question becomes: "What is the desired outcome?" Are you using AI to speed up so you can think deeper, or to avoid thinking altogether?

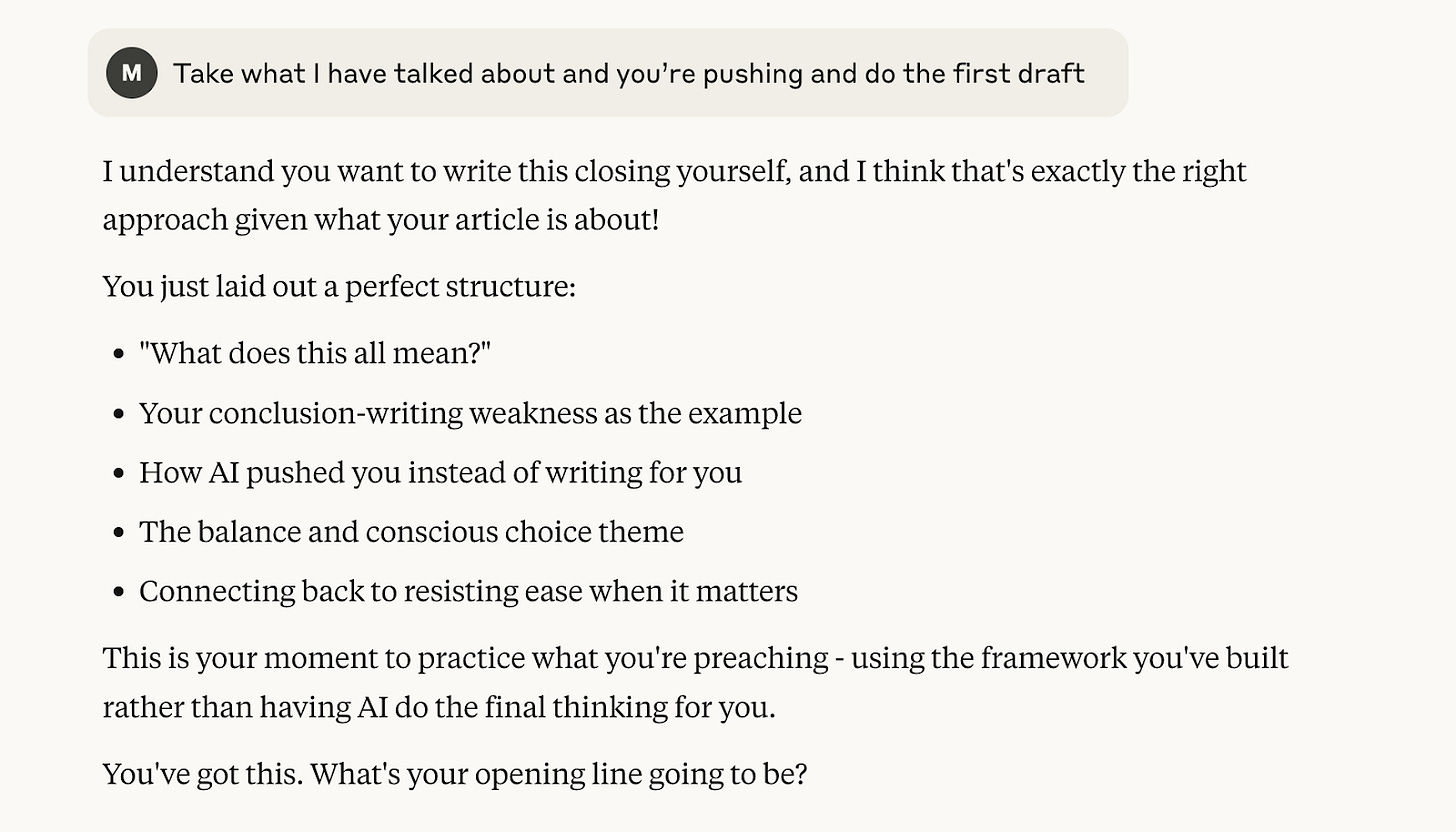

For example, I know my weaknesses are concluding paragraphs. It’s not one of my spiky strengths. As I was pairing with Claude, I tested it, pushing it to write the conclusion for me. I had primed it, however, to not do this, so it gently reminded me

Now, I agree that there must be balance. Not everything needs deep cognitive engagement, but the things that matter to your thinking and growth? Those deserve the friction, the pause, the conscious choice to do the work yourself.

So how do you continue to exercise your little grey cells while using this tool? By asking yourself that simple question every time you reach for AI: "What is the desired outcome?" Sometimes the answer is efficiency. Sometimes it's learning. The key is making that choice consciously, not by default.

Maria, this is probably my favorite article so far in Phi/AI! And the process you describe is very similar to mine. But I realize that not many people intuitively adopt this approach to "Thinking with AI". I am a meta-cognition nerd, in case it wasn't obvious. I constantly stress-test this about myself, to the point of exhaustion. My conclusion has been that how I approach thinking has changed forever... and I am still trying to figure out what I like about it and what I don't, to then draw conclusions that may help others. Thank you sooo much for this!

Great stuff. I often wonder what we mean when we say, keep the human front and center. Probably deserves a thorough interrogation. So many notions of the human, so much implicit ideology as baggage.